Like most everyone on LinkedIn, you’re probably a busy professional. You end your days exhausted from too much admin, too many Zoom meetings, and too much to do. BUT, you’ve found five or ten minutes to scroll through LinkedIn. And maybe after you’ve “caught up” on here, you’ll move on over to Insta or Facebook, or the place where all productive time goes to die, TikTok.

If you’re reading this for a little scheduled break in your day, or because you are actively using LinkedIn for professional development, that is one thing. However, if you are just here for a quick curiosity hit, you may be using LinkedIn to satisfy your Restless or Avoider saboteur.

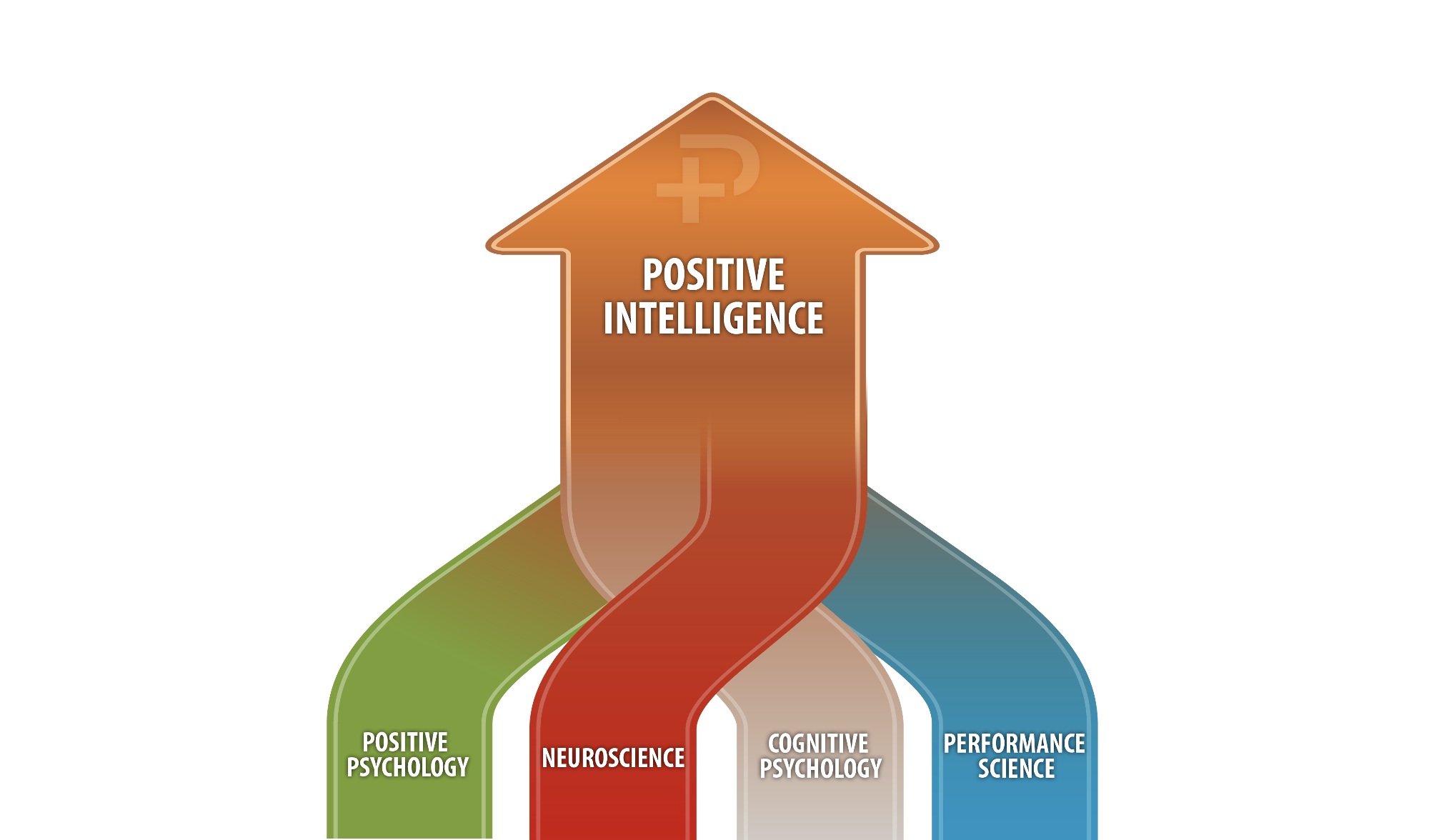

What is a saboteur you ask? A saboteur, in the language of Positive Intelligence, is the voice in your head that says you can engage in emotionally negative behaviors because they are somehow good for you. For example, have you ever told yourself, “I deserve just a little break before I move on to write my expense report” and then realize you’ve been scrolling for an hour?

Our generation is perhaps the most distracted ever. Some of that is because big tech knows how to hook us on mini-serotonin hits that keep us engaged on social media. Some of us are just wired to more quickly give into temptation and grab a quick distraction. We go to these sites in order to satisfy our own inner voices telling us we can indulge in something silly right now instead of doing the things that are more fulfilling or satisfying long term.

We call those voices the “Restless” and the “Avoider” saboteurs. The Restless saboteur tells us that greater satisfaction is just around the corner, if we just could get away from the current project or current conversation and find something more meaningful. If we’re at a cocktail party, we are always looking around for someone one else who may be more valuable or more interesting. If we’re working on a project, we can quickly find other projects that appear to be more fun, exciting and motivating.

Of course, we all know where that ends. We have trouble making real connections, or even fully engaging with people because we are looking over their shoulder for someone more valuable to talk to. Our friends and coworkers sense that and think of us as aloof or worse, snobbish and arrogant.

If you have the Avoider saboteur, it tells you that momentary pleasure from a diversion is better for you because it removes the pain of dealing with difficult situations or substitutes pleasure for tasks you might see as drudgery.

Both of these saboteurs do have a positive side. If you have the Restless saboteur, for example, that same saboteur likely means you are interested in a lot of things. You can be creative and are excited by new projects and people. You’re open to new ideas and hungry for stimuli.

The Avoider has bigger challenges since a lot of the Avoider saboteur lurks in inaction rather than in activity. The Avoider though loves peace and calm. The avoidance of conflict can be an inspiration to consensus and group harmony,

When used in coaching, we feel it’s important that we not label people as Avoiders or Restless, or any of the other seven saboteurs. We each have some of these saboteurs, in smaller or larger quantitites, within us. The trick is to become aware of their voices and stop them before the worst parts of them hijack our emotions and then our actions at work and at home.

In Positive Intelligence, we use testing to more quickly identify the strongest of the saboteurs. We learn to identify when they are speaking the loudest. The next step is to use CBT-style techniques (Cognitive Behavior Therapy) to try to change our reactions to the voices. Over time, MRI imaging shows that we can actually change the grey matter in our brains and learn to turn the negative voices into wiser and more generous responses to even negative stimuli in our lives.